Explanation of the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido 3 Kawasaki

9.8km from Kanagawa to Kawasaki, 35°32′08″N 139°42′28″E

Kawasaki is the second post station on the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido.

It is currently in Kawasaki Ward, Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture.

The post station had two honjin , 72 hatago, 541 houses, and a population of 2,433.

At the time the Tokaido was established, it was not a post station.

The distance between Shinagawa and Kanagawa was 10 ri round trip, which was a heavy burden on the horse-drawn carriages.

Kawasaki was officially established as a post station in 1623.

After its establishment, the burden on the farmers who drove the horse-drawn carriages was so great that the wholesaler’s office was forced into bankruptcy.

In 1632, the post station officials appealed to the shogunate to abolish Kawasaki.

The shogunate provided support for the wholesaler’s office and other facilities.

However, the request to abolish it was rejected, and the burden of the horse-drawn carriages was further increased.

Earthquakes and the eruption of Mount Fuji caused financial difficulties.

Tanaka Kyugu, who served as a wholesaler, village headman, and head of the honjin, lobbied the shogunate to give Kawasaki-juku the rights to the Rokugo ferry.

He also played a major role in rebuilding Kawasaki-juku, such as obtaining relief funds.

The maintenance of Kawasaki-juku also places a burden on neighboring farmers as assistant villagers.

When the system was launched in 1694, it was divided into eight villages of Josuke-go, which were called up first, and 30 villages of Daisuke-go, which were used in cases where Josuke-go was not enough.

The burden on the villages of Josuke-go became too great due to the increase in traffic on the Tokaido, and in 1725 the division between Josuke-go and Daisuke-go was abolished.

Later, 16 villages further away were ordered to become assistant villages.

The allowances given in return for the burden of the assistant villagers were negligible.

During that time, they could not do any farm work.

A problem particular to Kawasaki-juku was that if the Tama River was blocked off, they would be detained for days.

The burden was so heavy that some people applied for exemption from the Sukego service or simply filled out their attendance records and ran away.

They took steps to avoid the burden.

The amount of money they had to pay was high, and Sukego village continued to suffer.

Kawasaki-juku was made up of four towns: Sunago, Kunezaki, Shinjuku, and Otoro, and the main inns were Tanaka Honjin, Sato (Sozaemon) Honjin, and Sobei Honjin.

Sobei Honjin went out of business in the late Edo period.

Due to repeated disasters and the financial difficulties of the various domains, the Honjin also declined by the end of the Edo period.

In 1857, Townsend Harris was scheduled to stay at Tanaka Honjin.

It was decided to move to Mannen-ya due to its dilapidated condition.

This Mannen-ya was located at the junction of the Tokaido road to Kawasaki Daishi, and it prospered thanks to its advantageous location.

In 1877, Princess Kazunomiya and her son stayed there, and it was said to have caused the Honjin to decline, and it boasted of its prosperity.

In 1882, it disappeared due to the construction of the First Keihin Highway.

A conflict arose between ordinary hatago inns and food-selling hatago.

There were 72 hatago, and 33 of them were “food-selling hatago” that employed food-serving girls, concentrated in Shinjuku.

There were 39 “ordinary hatago” that did not employ food-serving girls.

Each hatago was limited to two food-serving girls, but in reality this was not observed.

Dress became so extravagant that crackdowns were necessary.

Food-selling hatago continued to operate in the same way as “rented houses” in the Meiji period.

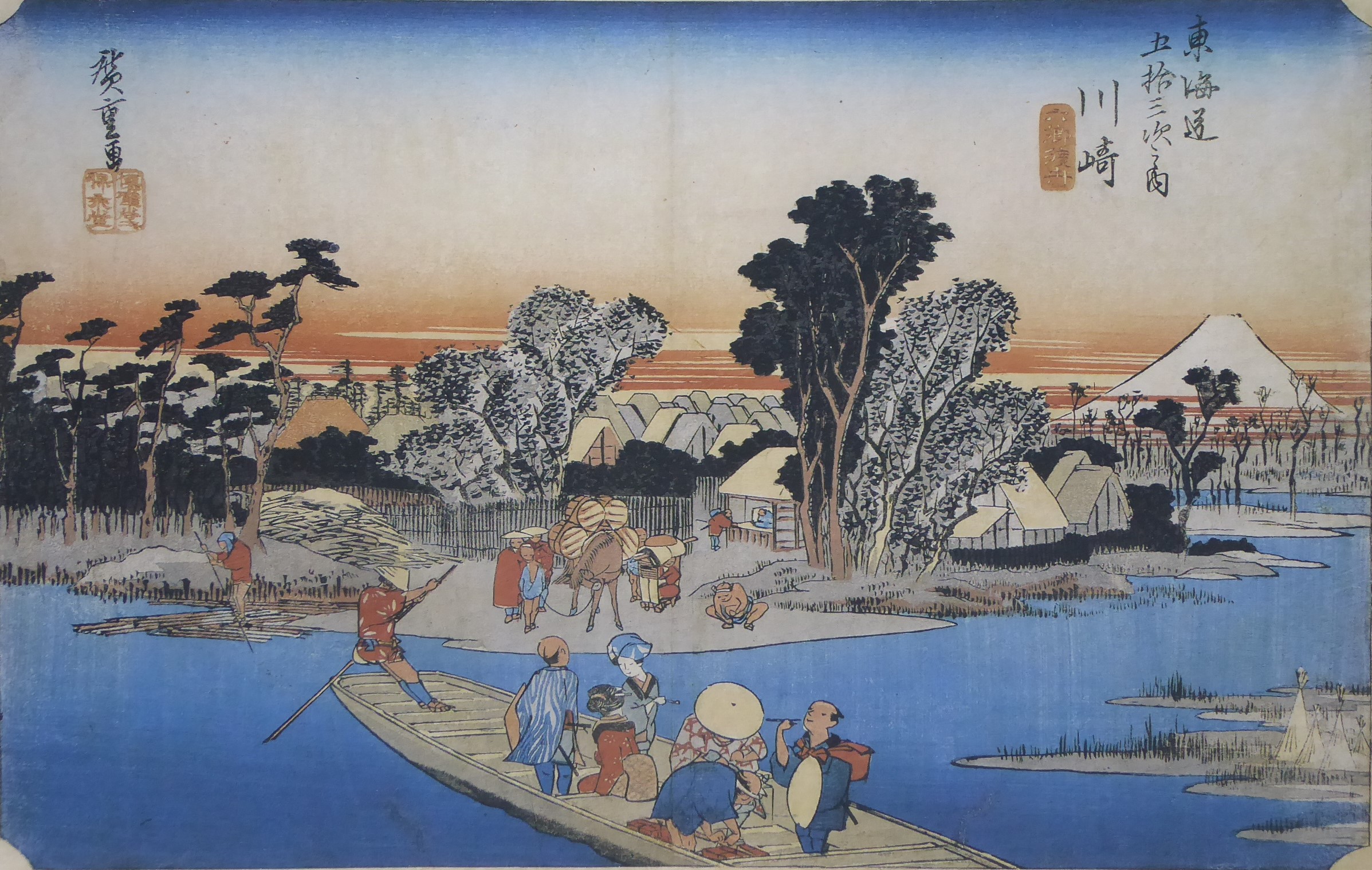

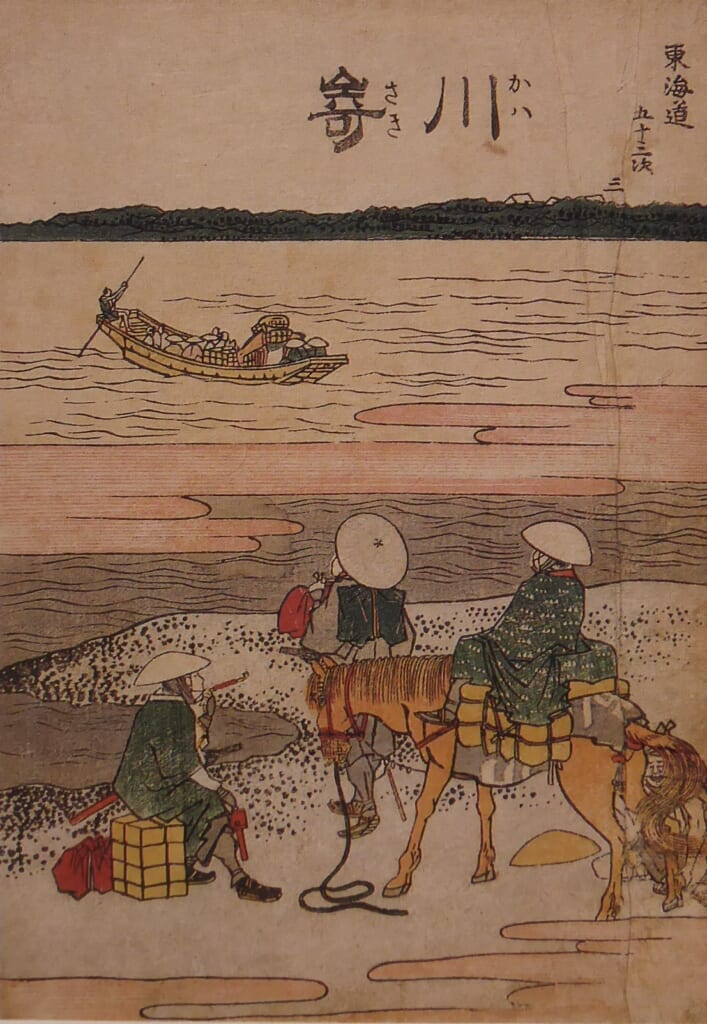

① “Hoeido version”

It depicts a ferry across the Rokugo River just before entering Kawasaki-juku.

The first large river to cross on the Tokaido is the Rokugo River, downstream of the Tama River.

Kawasaki-juku can be seen on the opposite bank.

The boat that crossed was called the “Rokugo Ferry.”

The ferry cost 10 mon per person, but was free for samurai.

When Takeda Shingen’s Koshu forces attacked, the Hojo side burned down this bridge.

The bridge was later restored during the reign of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The bridge was frequently washed away by floods.

As a result, people began to cross the river by boat.

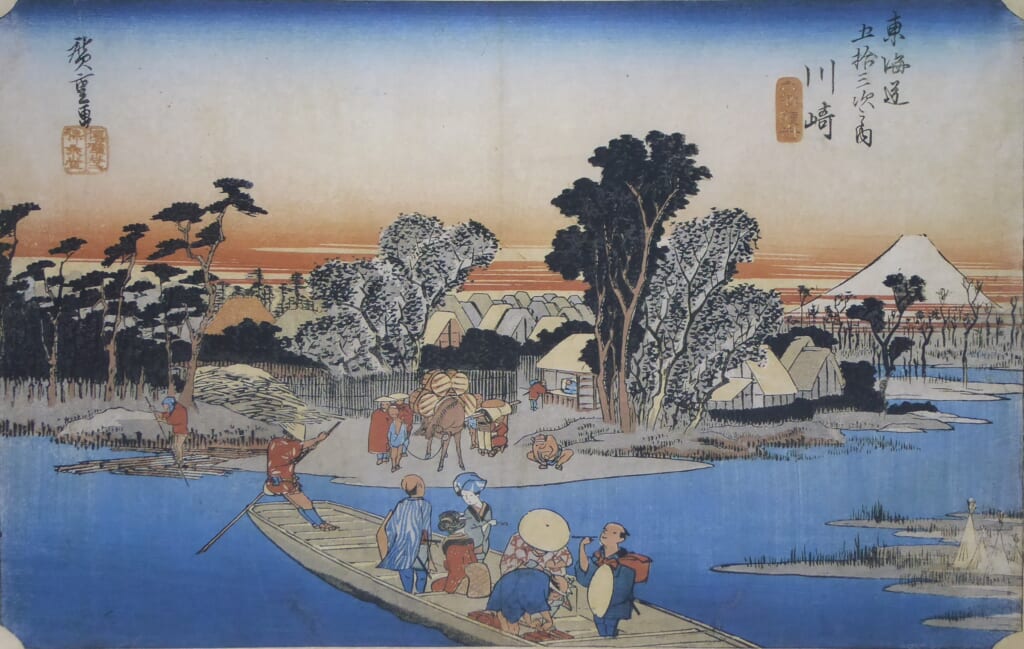

② “Gyousyo version”

This depicts the ferry across the Rokugo River just before entering Kawasaki-juku.

It is drawn from a low perspective.

It depicts two ferries passing each other.

Mount Fuji can be seen in the background.

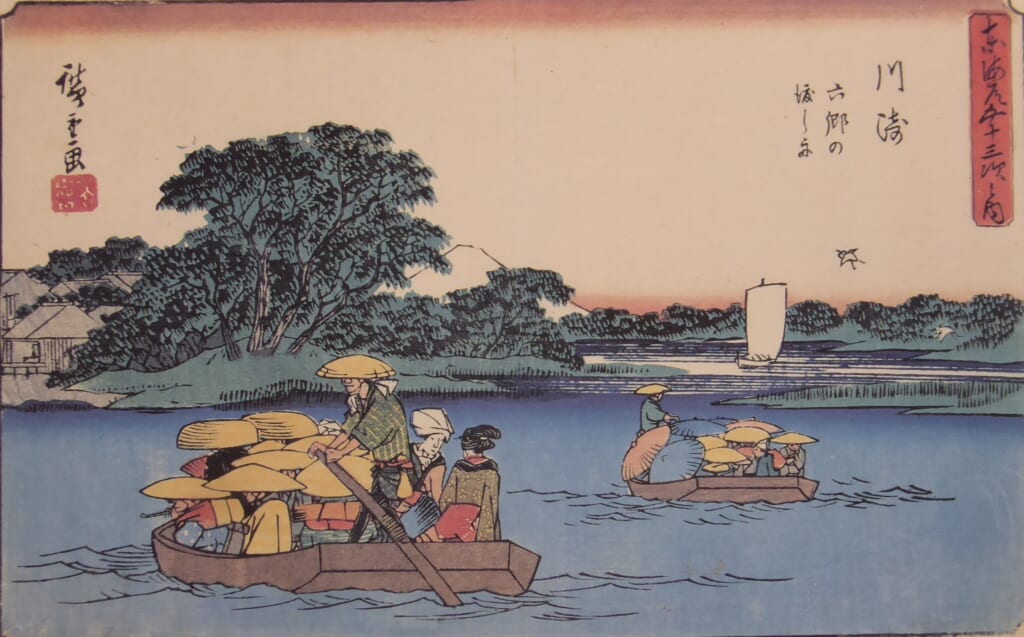

③ “Reisho version”

Both banks are drawn, with the ferry boat drawn from the side in the center.

You can get a good idea of what was happening inside the ferry boat. The large sailing ship expresses the depth of the river.

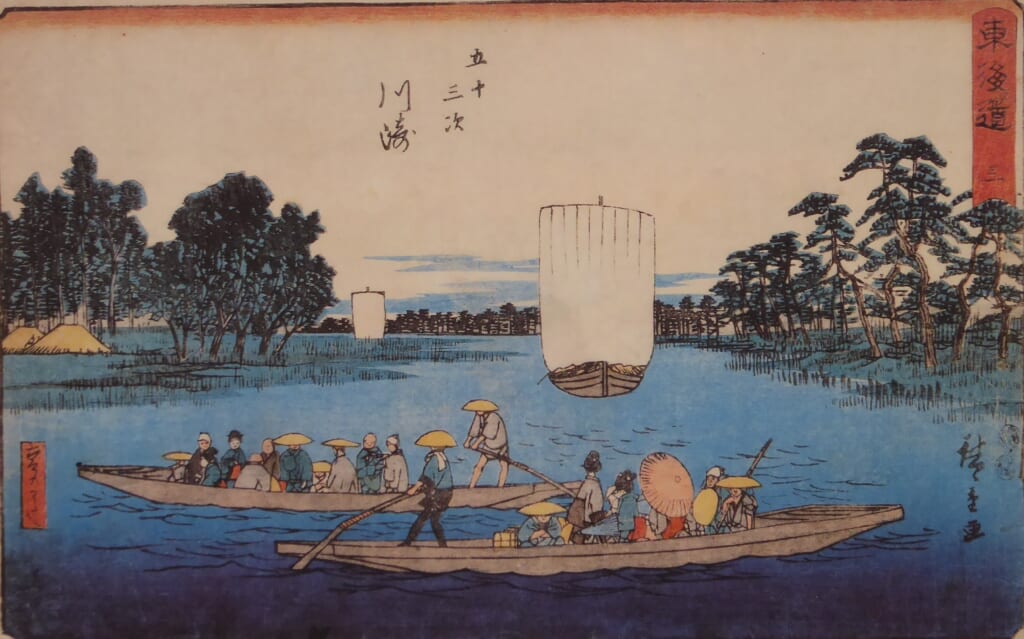

④ “Hokusai version”

The scene depicts a ferry crossing the Rokugo River.

A traveler is waiting for the ferry to arrive.

⑤ “Travel image”

A guide board for Hachonawate.

⑥ “Stamp image”

A stamp from JR Kawasaki Station.

Hoeido version

Gyousyo version

Reisho version

Hokusai version

Travel image

Stamp image