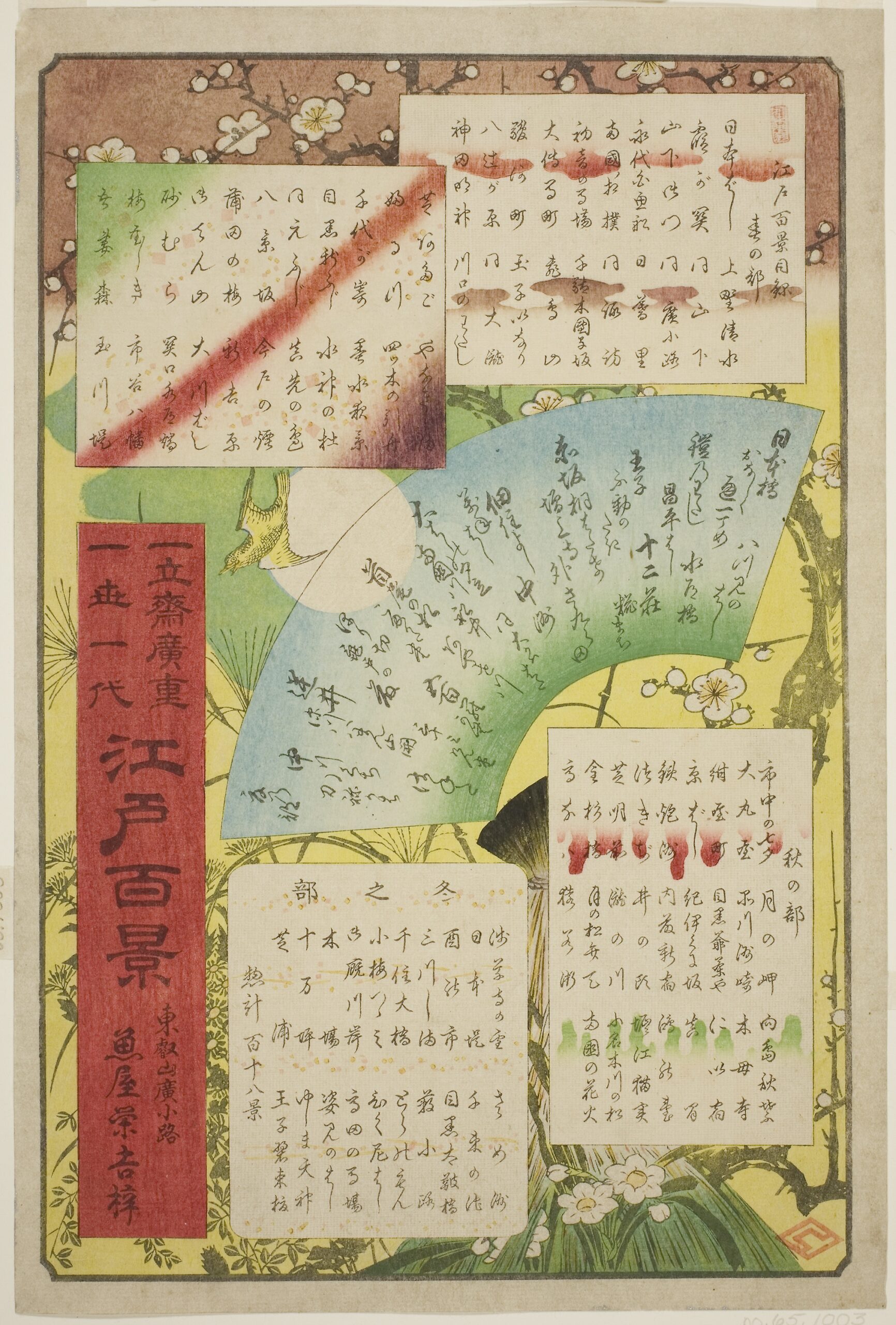

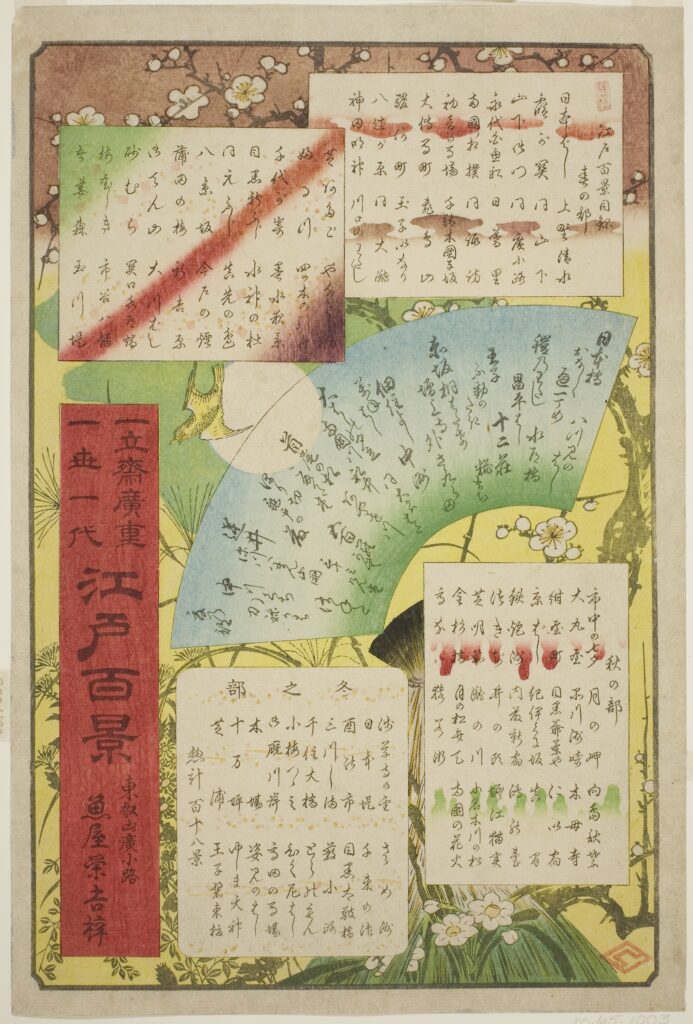

Utagawa Hiroshige – One Hundred Famous Views of Edo – General Commentary

Utagawa Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige is a representative ukiyo-e artist of the late Edo period.

His real name was Ando Juemon. He was also known as Ando Hiroshige.

He studied under Utagawa Toyohiro and specialized in landscape painting.

His masterpiece, “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road (Hoeidō Edition),” skillfully depicts the various post towns and natural scenery.

He strongly stimulated the desire of ordinary people to travel.

Hiroshige’s style is characterized by delicate colors and lyrical expression.

He excels in depicting weather conditions such as rain, snow, and twilight.

In his later years, “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo,” he painted Edo landscapes with bold compositions, influencing Western impressionists such as Van Gogh and Monet.

He remains highly regarded worldwide as a lyrical landscape painter who closely reflects the perspective of ordinary people.

About “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”

“One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” is a series of 119 paintings that began publication in 1856 and continued until Hiroshige’s death in 1858.

Arranged in the order of “Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter,” the series vividly depicts Edo’s beloved famous places and the lives of ordinary people.

In fact, the series exceeds “One Hundred Views,” a reflection of Hiroshige’s vigorous creative drive and his desire to encompass the landscapes of Edo.

A key feature of this series is its innovative composition and color sense, which go beyond traditional paintings of famous places.

Large bridges and trees are placed in the foreground, with the cityscape and distant scenery beyond them depicted, giving the painting a sense of depth and dynamism.

Furthermore, the series’ use of sudden bird’s-eye views and extreme close-ups demonstrates Hiroshige’s originality in freely shifting the viewer’s perspective.

These techniques were later introduced to Europe, where they had a profound influence on Impressionist painters such as Van Gogh and Monet.

His subjects include Edo’s iconic Nihonbashi and Ryogoku bridges, the banks of the Sumida River, Sensoji Temple, Ueno, Shinagawa, and Shiba.

These were places that common people of the time visited on a daily basis, as well as festival sites.

Many of his paintings skillfully incorporate natural and climatic scenes, such as cherry blossoms, autumn leaves, snowscapes, fireworks, and sudden showers.

Scenes in which the landscape and people’s lives are integrated are vividly depicted.

Works such as “Shower at Ohashi Bridge and Atake” and “Plum Shop at Kameido” are particularly known as Hiroshige’s masterpieces, and have received high praise worldwide.

Even more noteworthy is the way this series is seen from the perspective of ordinary Edo people, cherishing their everyday pleasures and a sense of the seasons.

Rather than magnificent landscapes for the powerful, these are emotionally rich depictions of scenes where ordinary people actually walked, played, and lived.

They struck a chord with people of the time. It rediscovers the charm of the enormous city of Edo.

At the same time, it has value as a cultural record that demonstrates the maturity of urban culture.

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo continued to be published until shortly after Hiroshige’s death, and is considered the culmination of his final years.

Its innovative composition and lyrical depictions go beyond mere landscape paintings and have been passed down to future generations as “memories of Edo,” leaving a significant mark on the history of Japanese art.

Today, it is held in many art museums both in Japan and abroad, and continues to influence artists and viewers worldwide.

It is particularly held in many overseas museums. Not many remain, as they were damaged and burned in the Tokyo air raids during World War II.

However, they have been carefully preserved by overseas collectors and remain in overseas museums.

Hiroshige’s life revolved around the scenery of Edo. He began publishing pictures of famous places in the eastern capital at the age of 36, and continued to paint them until his death.

If he had not died at the age of 62, he might have been able to complete “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” and “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, Part 2.”

It took him about three years to complete 118 drawings, so I think it would be possible if he had lived another three years.

Works (Start End)

Famous Places of the Eastern Capital (1832, age 36, 1838, age 42)

(50 prints in total) 東都名所

Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido

Hoeidō version (1833, age 37, 1834, age 38)

gyousyo version (1839, age 43, 1842, age 46)

reisyo version (1847, age 51, 1852, age 56)

(55 prints in total) 東海道53次

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1856, age 60, 1859, age 62)

(119 prints in total) 名所江戸百景

Here are six reasons why ukiyo-e prints of famous places were so popular, in addition to the fact that Edo was a popular subject.

First, many of them were located within easy travel distance for Edo’s commoners.

Second, samurai on their alternate attendance routes purchased them as souvenirs and mementos.

Third, they were gifts for local commoners who came to Edo for tourism or business.

Fourth, they are valuable as documents of Edo’s “customs,” “culture,” “annual events,” “famous products,” and “people.”

Fifth, ukiyo-e prints were inexpensive, costing about the price of lunch.

Sixth, ukiyo-e prints were light and easy to carry as souvenirs.

The order of the paintings this time is “Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter.”